Viola Delaine was designed to be a contradiction—gorgeous yet self-conscious, talented yet insecure.

Like I mentioned in my previous article, her story was inspired by my wife’s struggles with finding a bra that fit, along with the frustration of feeling creatively stifled as a bookkeeper. As I developed the script, I leaned into that theme—someone who didn’t quite fit anywhere—at work, in her clothes, or even in her own skin. She wanted to be seen but feared what others might notice. Always hiding, afraid to expose her flaws, yet longing for someone to recognize her—not just as a bombshell, but as a seamstress.

Since Hidden Curves is set in a 1940s/50s noir world, I had a rich tradition of femme fatales and classic Hollywood starlets to pull from. But Viola was more Audrey Hepburn than Marilyn Monroe—closer to a modernized Betty Boop than a Jessica Rabbit. She downplayed her femininity with an unconventional pixie cut, buried her figure under a big fur coat, and wrapped herself in a thick layer of social awkwardness.

My first sketches leaned into whimsical exaggeration, inspired by Mary Blair, Al Hirschfeld, and Shane Glines. Fun, but too playful for a noir.

She needed depth and subtlety—expressive enough to carry the story but grounded enough to belong in a black-and-white comic about crime and couture.

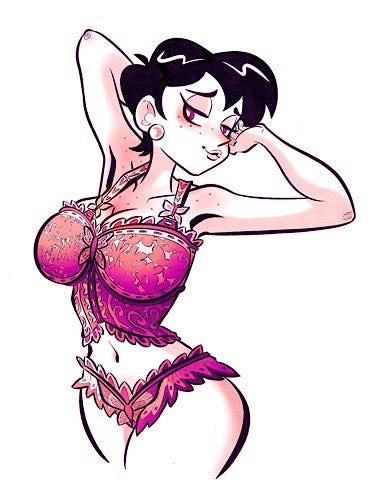

Then came another challenge: If the female form is a key theme, you better know how to draw it.

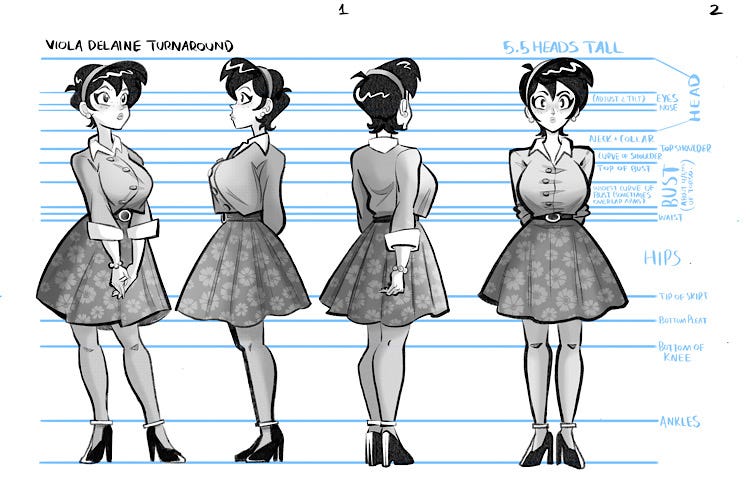

I realized my anatomy work wasn’t where it needed to be, so I tightened up her proportions, did a full turnaround, and refined her expressions. Once I had that foundation, I put her through a “test run”—pinups, character studies, and expression sheets—figuring out how she carried herself when anxious, confident, or caught off guard.

In the end, designing Viola wasn’t just about making her look right—it was about making her feel real. Someone whose story you can hopefully see just by looking at her.

Next time, we’ll dive into the challenges of designing the rest of the cast!